Monty Richthofen, aka Maison Hefner, is a modern-day poet and tattoo artist reminiscent of the late Jean-Michel Basquait whose sardonic spray-can commentary on life in the late 70s and early 80s in Lower Manhattan made him so famous he burned through the art scene like an asteroid until his death aged 27.

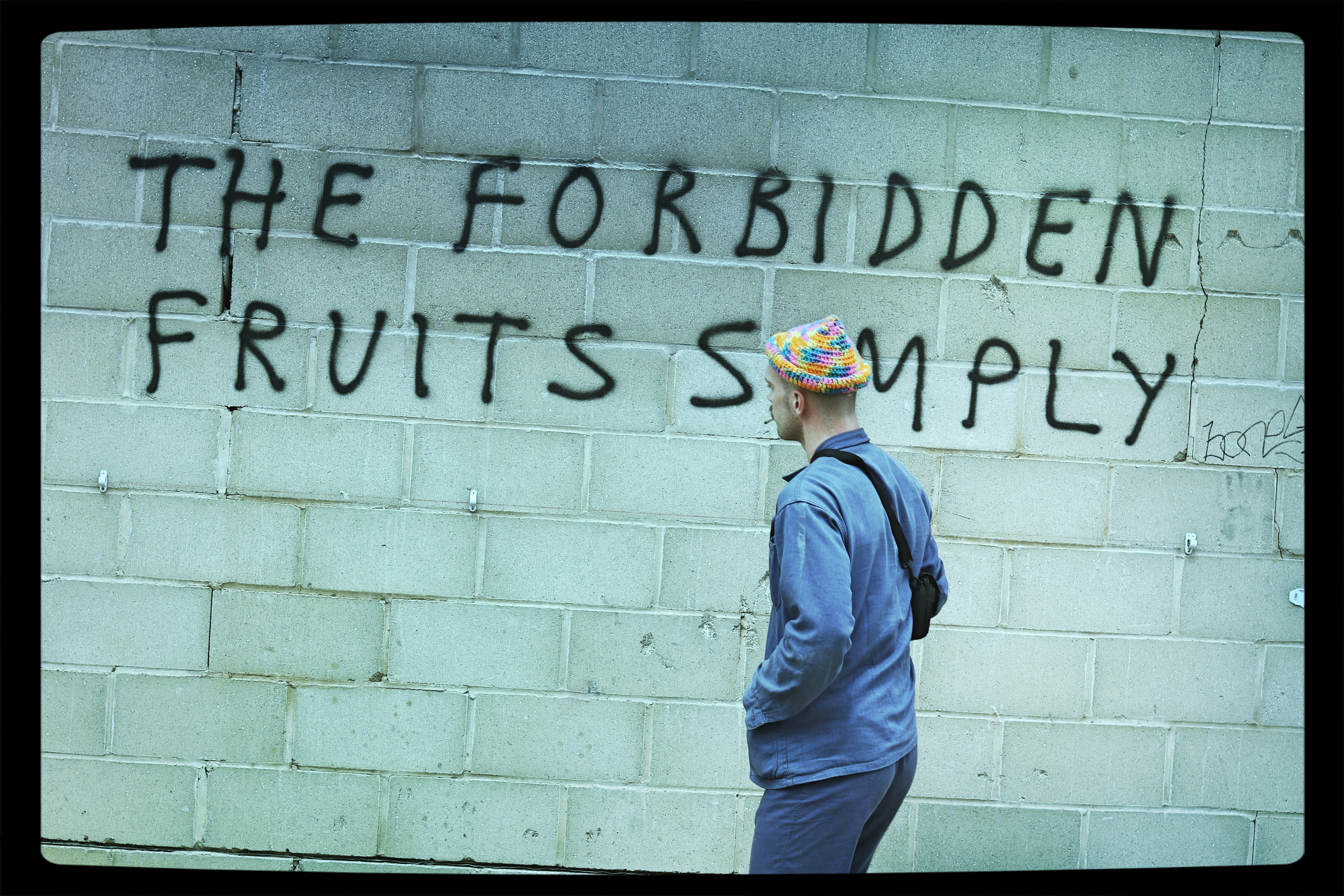

As Basquait did under the tag SAMO, Monty has put a kaleidoscopic spin on clichés, weaving them into millennial dog-whistles of witty ambiguity and cutting social commentary so deft he’s become the Pied Piper of the internet-age.

Cherub-faced and just 23 years old it is no surprise Monty’s musings speak to the hearts and minds of a culture so vacuous it can be ensnared in a handheld device – but Monty, just like his minimalist tattoos, is so much more than clever word-play.

He is whip-smart and tender in a way tattooists seldom are with a utopian view of a trade so infectious you can’t help but believe he might know how to free it from the shackles of tradition without letting it get crushed by commerce.

PART I – The Spew-Up That Captured Monty’s Imagination

Monty’s desire to leave a mark was born in Aix-en-Provence, on a bus ride with his chums to a boarding school he’d been sent to from his native Munich age 15. He recalls marvelling at his classmates rubber-necking to catch a glimpse of a wall defaced with a graffiti throw-up another student had painted, “and I was like, ‘wow, cool’.”

The student taught Monty how to sketch then he went solo.

“I kind of realised that creative expression would be part of my life when I realised it was much more fun to go and paint a train by yourself than go with all your friends to a bar to drink Grey Goose and get into fights with French guys,” Monty recalls.

Graffiti led to tattooing, something Monty had no previous interest in. A few of the older boys in the boarding house had ink, but he thought it was “super trashy”.

In Berlin a graffiti artist Monty knew offered to tattoo him, “and I was like why not” and after the next one also chose a spot on his flesh to mark, he asked Monty to reciprocate.

“I was like, ‘hey I’ve never tattooed before’ and he just said, ‘there’s always a first time’. And this statement really convinced me, because there always has to be a first time.”

Monty tattooed a star holding a bottle with the words ‘funky stuff’ written underneath, but because he didn’t know how to use a stencil the image was mirrored: “After that I didn’t tattoo for quite some time.”

Monty was accepted into a media studies course in Edinburgh after high school but he never made it to class, realising part way through the course that he had “completely forgot while I was in Berlin painting graffiti, taking heaps of drugs and meeting my ex-girlfriend”.

Monty credits his parents with teaching him curiosity and in Berlin he found a wonderland to explore, age 18: “It was the first time I was confronted with actual subcultures. It was the first time I was confronted with real partying, real graffiti, real train writing. I didn’t look for anything it just came to me. I wasn’t trying to belong to anything, I was just open to experiences.”

He continued: “For my age I already knew at that point what I wanted to do. At that moment it was to paint and express myself and to put myself in situations that I was not necessarily comfortable with because it brought me excitement.”

Graffiti taught Monty the non-technical skills of tattooing – to take risks, to stand by his work – but marking walls was temporary, unlike skin, and the artist wanted his work to have longevity.

Graffiti taught Monty the non-technical skills of tattooing – to take risks, to stand by his work – but marking walls was temporary, unlike skin, and the artist wanted his work to have longevity.

“With graffiti you can’t create what you intend to with tattooing. With tattooing you create something that is quite permanent, at least it leaves a mark you can’t just wipe off… unless you have very good laser treatment… so you achieve something that is not possible with graffiti. Something that people see, and something that people carry with them always.”

After being tattooed in London by @luxiano31 – a Mexico-based artist whose background in graffiti is still evident in his work – Monty decided to tattoo full time despite having almost no experience.

“The biggest thing that stuck with me, that he said, was if you want to do it you have to do it with 100%,” Monty recalls.

Returning to Berlin Monty saved up for a tattoo machine and power supply and got started.

“I just didn’t tell people I wasn’t really able to do it, you know, fake it until you make it, trial and error. And that is what I did and through this trial and error I gained this confidence, and maybe it was this false confidence but if you don’t have any confidence at all you’re never doing to make it. Through believing, ‘why shouldn’t I be able to do it’, I just started and at some pint, quite quickly, people didn’t question it anymore.”

“I just didn’t tell people I wasn’t really able to do it, you know, fake it until you make it, trial and error. And that is what I did and through this trial and error I gained this confidence, and maybe it was this false confidence but if you don’t have any confidence at all you’re never doing to make it. Through believing, ‘why shouldn’t I be able to do it’, I just started and at some pint, quite quickly, people didn’t question it anymore.”

Monty’s signature phrasing came about after someone he was tattooing saw his distinctive handwriting, a cursive that has won him a cult-like following.

“They saw my handwriting and quite liked it and then a lot of people liked my handwriting. It was through graffiti I had this steadiness in my writing. In a way, you know, it was very pure. I didn’t try and style it and with the text, I never tried to style it either… I was just keeping it really simple.”

Early renderings included: Wave to cops then paint whole cars and French kissing in the club.

PART II – The Voice Of The Internet

Monty has never taken an art class. He studied theatre in school and while currently a student at London’s Central Saint Martins – where former alumni include, Alexander McQueen, John Galliano and Stella McCartney – he is studying performance practice and design.

Monty personifies this.

Just before midday on a Friday outside a brown-brick rabbit warren that claims to be artist studios and a gallery, but is more a flop-house, Monty appears with the chutzpah of a circus clown with bright red braces holding up a pair of oversized blue trousers, paired with a matching jacket, crowned with a woollen hat more fanciful of colour than a peacocks plumage.

The trousers and jacket are beat-up originals of the type first worn by railway men and engineers in France in the late 1800s. Simple and practical as their French name – bleu de travail (meaning ‘blue work’) suggests, the outfit has an unflattering silhouette, but on Monty, topped off with flyknit Nikes, it has been elevated to high fashion.

(Monty’s Central Saint Martins project, Who Am I Without You / Another You’ – which comprises of a five-minute video and an immersive installation said to give viewers a “window into a subculture that is unknown to most” – is shortlisted for the MullenLowe Nova awards that recognise fresh creative talent. From 1,300 graduating students, just five awards are presented to students whose work represents “truly original creative thinking and execution”. Voting closes on Tuesday – SUPPORT MONTY HERE. )

“I don’t think about a lot of stuff before I do it, just afterwards,” Monty says of his outfit, quickly directing the conversation back to his work.

“I don’t think about a lot of stuff before I do it, just afterwards,” Monty says of his outfit, quickly directing the conversation back to his work.

“So only when I started to do all of these writings I realised that I could put my visions and my desire for change, my criticism, in a positive way, into it.

“I just thought I have something to say. Especially after coming to London and seeing the gentrification… you see all of a sudden what it means to be in such a hyped place, especially in Central Saint Martins. Its such a hub and your confronted by fashion and trends and consumerism and coolness, or at least an attempt to be cool. And I guess I started commenting on that and people liked it.”

Monty’s lines are ponderings “that come through observations and conversations” he jots down in notebooks. When the pages are full, they’re closed. “I think it is quite nice, it’s a progression, you move forward… I move forward in my writing and in my tattoos.”

And they resonate with those raised on social media because he ignored it so long no one ever got sick of hearing his perspective on platforms often used to narcissistically calculate self-worth. By being a late-explorer of the digital landscape Monty’s observations carry none of the fatigue and rattle of the myriad of one-liners that have ricocheted and tumbled in re-tweets and re-posts.

“We have to start from the beginning,” Monty announces when asked about becoming the voice of the Internet.

The first confession: “I never had a Smartphone.”

“I was always very critical of my ex-girlfriend who was on Instagram. Before bed I would always tell her, ‘Why do you have this stupid phone? Put it down’. I never understood. Even when I started tattooing I didn’t have it (Instagram).”

When a friend made Monty an account, the circuit of conversation was complete: “I realised that this whole crowd that I want to criticise, or I want to awaken, they are all on the internet so this is why the internet became a very useful medium for me because I could reach the audience that I would not in real life.”

The flipside: “Now I’ve become part of this whole thing and now people are criticising me for being part of this Internet culture.”

While Monty is well-known for his catchphrase tattoos he also does bigger pieces that are arguably more controversial – unrefined renderings of the type that sit at the extreme end of ignorant art.

“The drawings I see very separate from the tattoos,” Monty explains.

“When I tattoo drawings I need to feel like this person is actually much more of a canvas and I like to do big pieces and I like to really go free. With drawings, for example, I don’t look so much at the technical aspect but much more at composition, much more at freedom of expression.

“With the writing its almost like I need to do it to get my thoughts out because by tattooing my thoughts on someone else they walk away with them to a certain extent. I can let them go. With the drawings, I don’t let them go. I quite like them.”

PART III – The Meaninglessness Of Markings

Monty has a tattoo on his upper thigh to remember his late father, who worked in film (The good may die young, but will never be forgotten) and getting it was a form of “therapy” he now tries to replicate with his clients in a process that sees him recreate the experiences he enjoyed and endured amassing his own collection.

“I let a lot of friends tattoo me that don’t know how to tattoo, because for me, again it doesn’t matter what is done, but who has done it and the situation under which they have done it,” Monty says of his own tattoos which include a rat fucking a cop, internet glasses, a chicken saying FTW and a variety of toilet stall-like doodlings.

“I’d rather have something, a memory from a girl that I was seeing than from some asshole tattooer that I have no connection at all with. Someone I just gave money to.”

“I’d rather have something, a memory from a girl that I was seeing than from some asshole tattooer that I have no connection at all with. Someone I just gave money to.”

This desire to make a connection, rather than just a mark, is best exemplified by Monty’s My Words Your Body project which sees him engage in an hour-long conversation with the client before encapsulating the experience, or their “essence”, in a turn-of-phrase.

I didn’t like having to explain to them, so I shut up and smoked a cigarette. #mywordsyourbody

A post shared by Florian (@noactuallycoolname) on

When Parloir first met Monty earlier this year we witnessed the unveiling of one such inking on a young girl called Alina who works in the field of domestic violence and abuse, and as Monty put it, “is a very helping and caring soul and this tattoo captures the essence of this person.”

When Parloir first met Monty earlier this year we witnessed the unveiling of one such inking on a young girl called Alina who works in the field of domestic violence and abuse, and as Monty put it, “is a very helping and caring soul and this tattoo captures the essence of this person.”

The tattoo seemed extraordinarily underwhelming and not worthy of such ceremony but the look on the client’s face when she saw it showed the mark Monty had left was more than skin deep. Alina cooed with excitement and gripped her belly with both hands as though to trap all the butterflies of happiness inside.

“The tattooing often it just takes ten minutes,” Monty confesses, after being questioned on what the client is actually paying for – words on their skin, or an audience with Maison Hefner.

“So it is a question of what you pay for. But the way I have started to think about a lot of these things… the tattoo doesn’t start from it being written down. There’s this whole experience before that I lived through that then leads to me writing it down, which leads to me tattooing it… or through conversation. So it has a life long before someone chooses it.

“Its like, for example, you raise a child. Before you let it out in the world you make sure they are ready… you need to make sure it is ready to leave the nest, or for this person to take this tattoo.”

For some stuck in the tight-pens of tattooing tradition, Monty’s taking the piss with his production line of street-poetry hipster-stamps. His work has featured on Sucky Tattoos, the re-post Instagram account that shames bad work rather than celebrate it, like Snake Pit.

“What a lot of people hate is that the writing takes, theoretically 30 seconds. To tattoo it takes 10 minutes. And so for me I can really quickly produce and produce and produce, whereas other people might spend six hours on a design. They redraw it. The customer doesn’t like it. So this brings frustration… ‘Why is he tattooing so much and gets all the recognition for something that is so quickly produced?’ But it’s the same with (Mark) Rothko, ‘Oh it’s just red paint’. But you didn’t just think of putting just red paint with maybe a bit more red paint.”

“What a lot of people hate is that the writing takes, theoretically 30 seconds. To tattoo it takes 10 minutes. And so for me I can really quickly produce and produce and produce, whereas other people might spend six hours on a design. They redraw it. The customer doesn’t like it. So this brings frustration… ‘Why is he tattooing so much and gets all the recognition for something that is so quickly produced?’ But it’s the same with (Mark) Rothko, ‘Oh it’s just red paint’. But you didn’t just think of putting just red paint with maybe a bit more red paint.”

PART IV – If You Don’t Know, You Don’t Know

Monty’s success lies in his ability to harness an arsenal of ambiguity to engage the imagination to the same extent it enrages tattoo purists. His flesh also speaks to this chaos over conformity ideal, with his tattoo collection equally confusing to those who want art to be the perfect technical execution of its subject matter.

“The idea is always much more important than the actual execution,” Monty explains, before championing the work of Auto Christ, the Israeli artist whose puerile scrawls seem executed under blindfold.

“A lot of the time people just simply don’t get it,” Monty says, as he sucks on a cigarette at the kitchen-table-come-desk in his bedsit that’s across the hall from his studio.

“For example, tattoos from Auto Christ, who I think is so avant-garde. He is one of the people who shook up tattooing in a very honest way. Never for trends, it is just his way. And either you get it or you don’t. If you need to explain it to someone they obviously don’t get it. And also, I don’t think you need to justify yourself for anything, neither as an artist or the recipient.”

Tattoos, Monty believes, “can be anything” and should be viewed beyond the actual act and the end result.

They are a conversation between artist and client, private from the funhouse mirror of social media where likes and follows monopolise ideals of merit.

“So, for example, works like, from Auto Christ, these people start to challenge these ideas of conventions and so for me, the reason why I would get something like this (a rat sodomising a figure of conformity – a cop) is simply to show I support this. I think it is funny. And for me, my body is not necessarily decorative it is more a collection of like-minded thoughts. The tattoos I have, the people that tattoo me, most of the time are very liked-minded, aesthetically or politically.”

While tattooing has a rich history marked across millennia, Monty sees it as just a medium and given it’s been the artistic expression of tribesmen, criminals, sailors and punks – all doyens of rebellion – he’s perplexed why some within the industry try and dictate how it grows.

The commerce that came with popularity seems like the obvious reason: Instagram supercharged stardom for artists and shops popped up like toadstools.

“There should be no conventions,” Monty states. “There should be respect for other people’s work but also you want to try and push the barriers. No art form progresses if you don’t push the barriers.

“It has always been a culture that was against the norm, but now there is a norm again. What I don’t understand is why do we want to keep a norm? As soon as you see a norm you should try and disrupt it, especially if you’re from an anarchist background, if you question rules, which I’d say a lot of tattoo artists naturally do.”

Monty wants tattooists to shun the conventions that have turned tattoo parlours into factories with masters and minions. He wants the client to become the focus, not just the canvas, and for the process to become much more than a consultation and a mark.

“You need to challenge everything, the techniques, the concepts, the placements and the environments people get tattooed in, but also the process leading up to the tattoo…there is so much to discover and I think we would really be digging our own grave as a scene by not encouraging this,” he says.

“I would love to get tattooed by someone similar to my approach because I think it taught me so much to know more about the people that I tattoo. It taught me so much about my own practice. Gave me so much more confidence about my own practice that I am surprised more people aren’t doing it.”

Change is the only way forward in a trade whose traditions are being eroded by the forces of gentrification like the high streets that surrounded the salons, and no one knows this more than the Voice Of The Internet – Maison Hefner.

“In the age of the internet you need to provide new stuff the whole time otherwise you will get replaced. If you continue to do what you are doing for three years, by the fourth year no one will talk about you. You will be forgotten.”