Liam Sparkes is at war – with everything.

Has been since he was a boy. Age 11 he sent a sketch of an armoured personnel carrier to the Queen. The London tattooist, raised on tales of conflict from grandparents who had manned frigates and parachuted behind enemy lines during the war, thought she might need it. She didn’t.

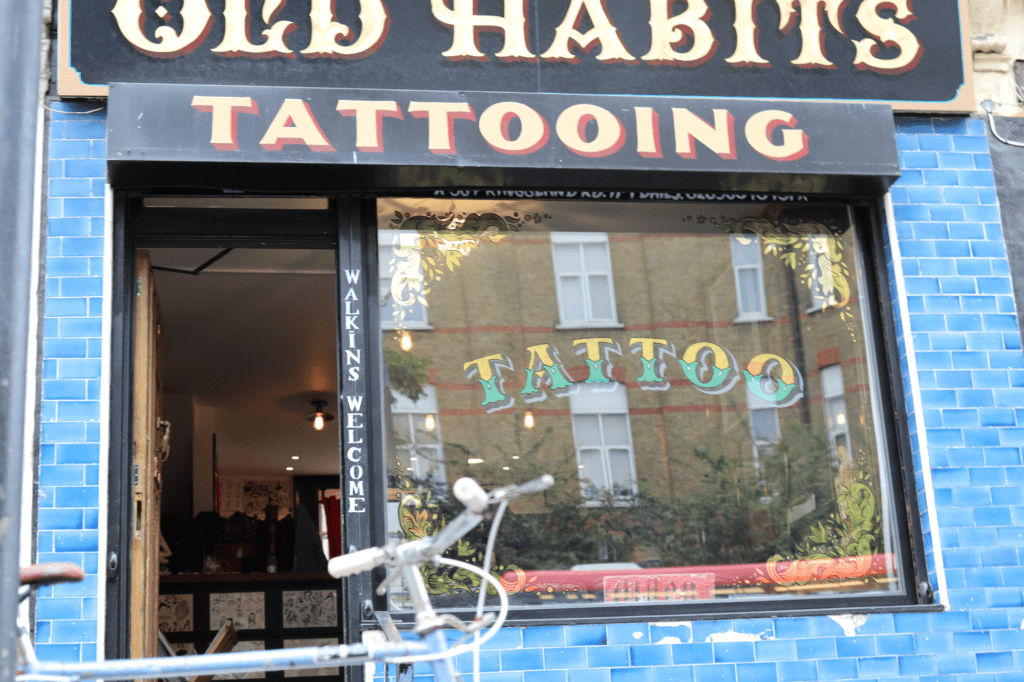

Slouching on the reception couch at Old Habits Tattoo, the east London parlour on Kingsland Road for which he is proprietor, Sparkes’ stories all tail-back to battle and even his 10-eye military boots, like his body, bear the scars of many tours of, not so much duty, but debauchery, for the 38-year-old’s appetite for destruction largely sees him seek and destroy – himself.

“I feel like life is war. It definitely feels like it, in every sense of the word,” he says fanging back fags.

“Going away to foreign countries. Fighting a war there. Getting a chopper out. Getting sewn back up at home base, then going back out for more. I like to go hard really and I really don’t know when it will stop.”

Sparkes’ party-boy reputation is well earned but it is a sideshow in the circus of his creative process that sees him dowsing in the darkness of his urges and sifting through the ashes of experience for the essence of his art. Not the beautiful kind that’s instantly admired and easily forgotten, but the brutality and absurdity imbedded in the ugly that sits in the throat and stains the subconscious.

“I am working 24/7,” he explains of his all-consuming approach that sees his art not so much imitate his life, but become it: “All the shit that I like to go and do comes out.” (Sparkes’ Instagram stories have the kaleidoscopic-styling of an acid trip – actuality not accidentally achieved by the auteur.)

He adds: “It’s more just a lust for life and I just feel like I need to get shit done, sooner rather than later, and thus the war on time, the war on myself, the war on life. War.”

Sparkes is admirably liberated and earnest as his eyes are blue in his pursuit of not only pleasure but professional and personal fulfilment. There is a method to his madness and it is of purity far stronger than the pills and potions he necks to fuel it, which is often all that is spoken of. For Sparkes, everything comes from the same cauldron, so everything must go in. Brutal tattoos, it seems, require a thick broth of experience for the applicator to draw from to ensure authenticity.

“That’s the truest… that’s integrity at the end. That’s the only way you should be. You have to do everything, with everything. You have to use everything you have as one thing. I couldn’t see it any other way really. You embody your art,” he explains.

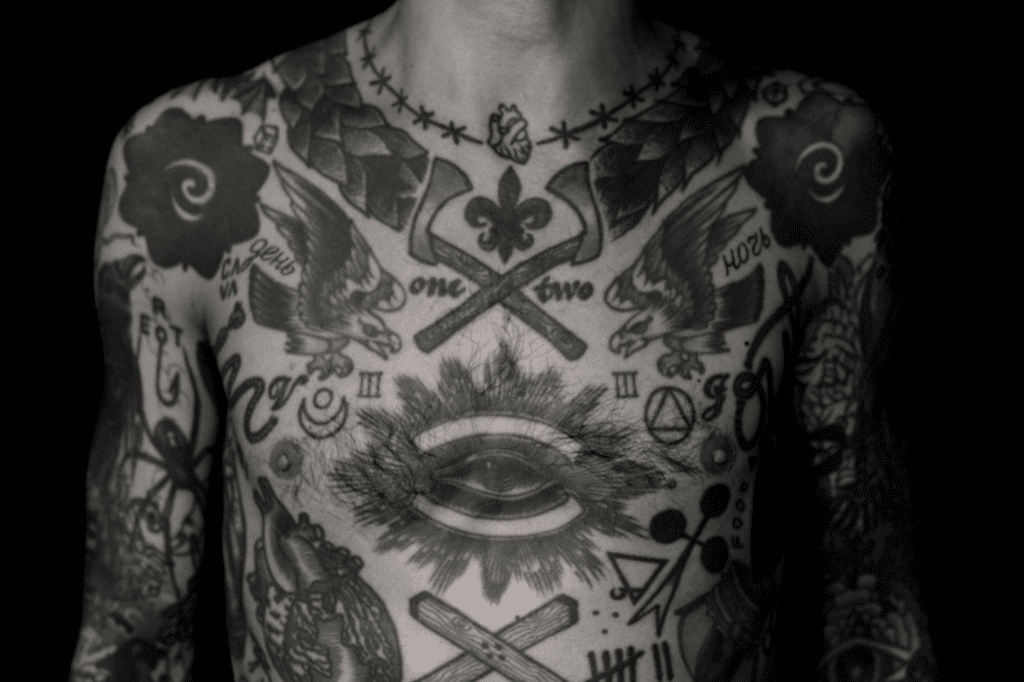

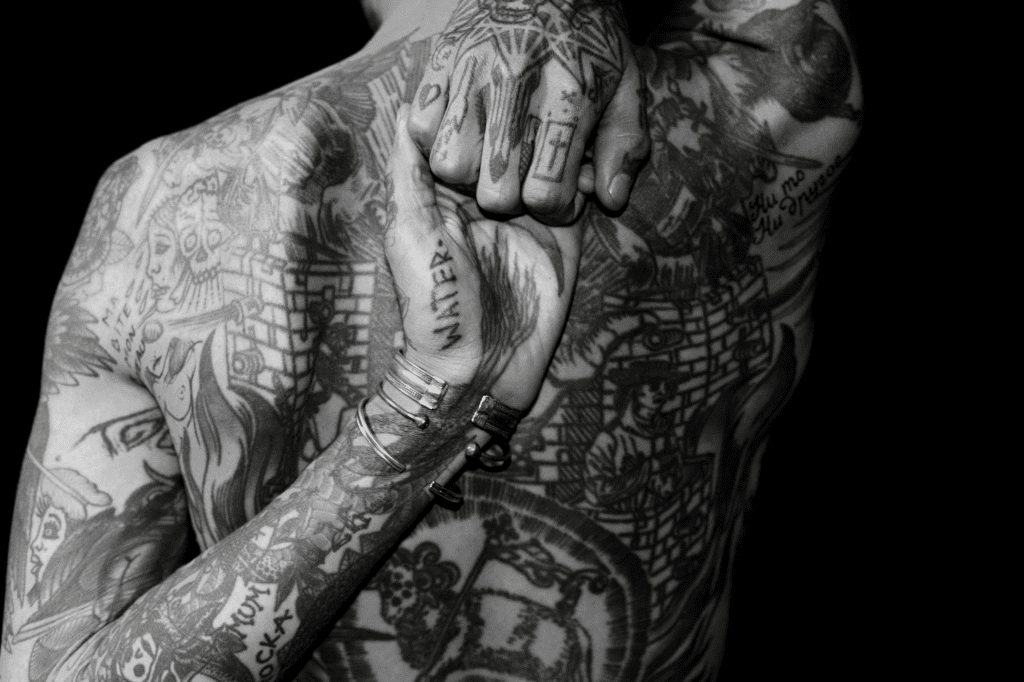

Sparkes doesn’t so much personify his art – he is it in its crudest form, exorcised and ready to die again. His body is a museum of the etchings of the early blackwork pioneers, Duncan X and Thomas Hooper, and his style owes a lot not only to them, but his grandparents stories, which are the genesis of everything.

“Everything that goes around war, such a terrible situation. The absurdity and brutality of it. I guess that’s where… I just think the ethos of my whole thing, life is absurd and brutal, you know, you just can’t help but laugh at everything and I think war is a perfect metaphor for the analogy. Absurd and brutal.”

Collecting tattoos, Sparkes opines, is a “destruction and an ornamentation of the body”.

“I realised when I started getting tattooed that this body is just a vessel and you can do whatever you want with it, and I was like, ‘why didn’t I destroy it sooner?’”

Everyone, Sparkes later explains stoically, “Deserves a chance to be destroyed”.

War craft were among the first things Sparkes drew as a kid. Soldiers later became thugs, the ugliness of their pronounced brow won him over: “It just looked better. And I guess that kind of works with the tattooing now. Bad, ugly, shit looks better than something mega hot, mega beautiful.

“I don’t know why. That’s my taste maybe. Beauty and imperfection, imperfection in beauty, maybe it’s a fascination with that.”

Russia, for those very reasons, keeps drawing Sparkes back – “this beautiful art, beautiful culture, coming from this brutality”.

AN INDECENT EDUCATION ON THE ROAD

After high school Sparkes studied sculpture for four years at Camberwell College of Arts before taking a job with the late Welsh sculpture Barry Flanagan, famed for his bronze statues of leaping hares.

The work, on a farm in Ireland, didn’t last: “I just remember thinking when I was doing sculpture, that I was doing this thing and I had no experience of the world. I did, but like only as a 20-year-old… how are you going to make sculpture when you don’t know anything about the world? It was kind of an absurdity at that time. So now, in some ways, I am just gaining more experience, for fodder, for the creative output.”

But even in his early 20s, Sparkes had experienced more life than many twice his age with a wanderlust inherited from his jeweller dad propelling him on lengthy solo trips around Europe. He was also beginning to find fame banging the drums in a band called Trencher under the stage-name, Lock-Monger. The trio got signed to Southern Records, put out three albums and were one of the last groups to perform a Peel Session in 2004.

The music was much like the tattooing style Sparkes would later become famous for: Brutally fast, deceptively complex, and absurd – songs included: ‘Fucking A Corpse’ and ‘I Lost My Hair In A Skiing Accident’. The band grew their audience on the road amassing a deranged cult-like following around Europe where they partied as if possessed.

“It was super-super debaucherous, like playing while completely fucked on mushrooms. Acid. Touring is just waiting around. There’s nothing to do in a band. None of us drove. So we had some of the craziest trips for weeks on end. Drinking hard when you got to the venue. Then sleep in some shit hole. And then do the same again.

“We’d do everything. Acid, mushrooms… not crack or heroin, well, opium, more or less everything expect crack… more or less anything we could get our hands on. We used to ask people in the crowd, as we were finishing, for drugs. Me and the bassist were fiends for it.”

PUTTING DOWN THE STICKS TO PICK UP THE GUN

Music was ultimately sacrificed for tattooing, an interest that grew like a vine into Sparkes’ mind before overcoming it completely.

At art school Sparkes met his mentor-to-be, Thomas Hooper, who was studying drawing but had already began tattooing professionally. Clean-skinned and unimpressed with the garish 90s ink he’d seen in the hardcore scene Sparkes began searching for someone who could do “engraving-style” tattoos. As it turned out, that’s exactly what Hooper did.

Sparkes got his first tattoo from Hooper in his early 20s. It was meant to be a red circle but Hooper filled it in so it became a dot. An all-seeing eye on his chest cavity was next and Sparkes was hooked: “Me and the wife were getting tattooed at the same time… it was kind of like a thing we did together. She’s got a lot from Hooper and a lot of old, good heads.”

Sparkes got married at 23, having met his bride-to-be, an American, at a gig in Brighton. She had Visa troubles they resolved in matrimony. Sparkes, who worked at Soho Original Books at the time, tells of the shotgun ceremony like it were a verse on Craig David’s Seven Days.

“I took a day off sick, on a Thursday. Took a flight to San Francisco. Married on a Friday. Went around shopping on Saturday. Flew back on Sunday, back in time for work on Monday. They (the shop owners) had no idea I had got married… had been in San Francisco for three days.”

The couple who “just wanted to be together and that was the only way it was going to happen” later moved to Kingston, in southwest London. The bookshop was a perfect job for Sparkes who educated himself behind the counter while also using the books as reference material for illustrative work he was doing for bands.

“It was a gestation period for where I am now because it made me sit down and focus,” Sparkes says, of the shop whose basement sold pornography and dildos, something that he says may well have “deadened me to vulgarity”.

Somewhat fittingly, now, more than a decade later, the basement of Sparkes’ business is littered with pornography. The toilets are a mosaic of 80’s smut cut outs and above the cistern, is a nativity scene-of-sorts: A crucifixion in space with lollipops, lays and a lizard mask. It is memorably absurd. On the ceiling above his workstation a woman uses her mouth to hold a metallic vibrator in place, inside the vagina of a co-performer resting on all fours, in turquoise high heels (Sparkes is adamant he did not put this up). The surrounding wall of the liar is a collage of offensiveness as though a perverted magpie had searched the globe for items shimmering with vulgarity to feather its nest. The mood board includes eight mug shots of women, next to pictures of their vaginas – a cunt-face comparison.

But in Sparkes’ presence the images are playfully un-offensive, rendered meaningless by his infectious mischievousness – mere checkpoints of a restricted morality that has no currency where old habits and dirty secrets are worn like war medals.

Sparkes bookshop-produced flyers were a hit and served to advertise his expertise more than the bands they were meant to promote, and later served as a calling card for fans seeking him out for tattoos.

“It didn’t really cross my mind (to be a tattooer),” Sparkes recalls, “every now and then I’d start designing my own tattoos which is a bad idea. But then I started designing tattoos for other people.”

Of designing your own tattoos, Sparkes opines: “I just think it is a terrible idea. You have this thing on you forever that you designed, and it’s your mistake. If someone else does it they’ll probably make it a lot better… otherwise you’ll be left with something on yourself that you made so you might as well have done a shit and you know, given it a name… I think it’s such a stupid thing when someone comes with exactly the thing they want.”

While out walking in Kingston Sparkes had an epiphany of sorts – he wanted to become a tattooist. Now he just needed to find the time: “Mostly life was music. We lived in a hardcore house. Everyone was touring. I didn’t really have time for tattooing.”

HOOP DE LOOP

Hooper told Sparkes what he needed to get started and that his first canvas needed to be himself. Serendipitously he then met Tas who was working at Into You Tattoo, but needed a drummer for his band. Sparkes joined his group and exchange was given a tattoo machine.

Sparkes began on his legs mainly doing “liney-Saints” and on a few close friends and poultry: “Hooper told me, ‘if you want to start tattooing it has to be your life’, and at that time I had this, that and the other going on, but then it just turned and I realised this is everything I want to do. And it became an obsession. I had to tattoo all the time. I used to buy chickens every night and tattoo them if I didn’t have any skin to do.”

Sparkes began doing consultations in the bookshop and “hustling in bars” and before he knew it he was tattooing six days a week from his Old Street apartment.

“It was ram jam. And after a while it got to the point that I didn’t need the bookshop anymore because I was making more at home than I was there, which was nothing… and I’d then spend all of my money on getting tattooed.”

Liam Sparkes Documentary from Ben Taylor on Vimeo.

Along with Hooper, Duncan X began tattooing Sparkes and the pair have been bonded ever since with the blackwork master now working at the station opposite his prodigy at Old Habits following the closure of Clerkenwell’s Into You last year.

“He (Duncan) was doing exactly what I was interested in. He was doing the stuff that I wanted to do. He was the originator of it. And also back then people who had tattoos from Duncan… it was like having a skateboard, or something. You spoke to each other because you had it. If you had a Duncan tattoo you knew you liked twisted black tattoos. And all of his customers were kind of like, a little bit awry.”

Sparkes continues:

“And he taught me so much. So many different principles of where we stand as doing blackwork. The offensiveness of it, which we both enjoy, but he taught me how to appreciate it. I’m not such a fan of offensive tattoos, or wasn’t, but now I really see that tattoos are offensive just from being like a scar on the skin, so in a way it is just like they are being true to themselves.”

Sparkes didn’t do a traditional tattooing apprenticeship but he effectively managed his own education flying to the States to observe Hooper hone his craft at New York Adorned, while also getting his own blackwork suit fitted.

“I’d stay in squats, maybe tattoo a few people in the squats in Brooklyn, then go and get tattooed by him, then I’d spend all my day watching him in the shop. He’d let me sit next to him, or in the corner, for weeks at a time. And I’d not do anything else. That was the main way to learn, just watching him pull lines… and then doing it myself, making mistakes and learning from it.”

Sparkes can’t speak highly enough of Hooper, whose “technical ability is flawless’, and Duncan X: “I’ve always made it known that Hopper and Duncan are my inspirations. And it is important to keep the history alive like that, by telling who the originators are. And that’s why I’m so happy now that Duncan has had his comeuppance from all these years. You used to be able to walk in and get a tattoo from him the next day, now you have to wait a year or something.”

After divorcing his wife of six years, Sparkes moved to Brick Lane where he continued to build a following, working out of a flat he shared with a Polish girl, above a taxi shop. He worked six days a week taking only Thursdays off to drop acid and sell books in nearby Spitalfields market, “just to get out of the house”.

“So, the book selling didn’t go well,” Sparkes recalls. “I’d just take acid and end up with no books. Well, the one’s I didn’t want anyway. I started making less and less money… I was tripping balls… but I was just working myself to the bone six days a week and it was just to get out of the house, so it didn’t matter.”

THE SHANGRI-LA DAZE

When Sparkes got too busy working from home he went to Shangri-La Tattoo in Shoreditch where he showed them a portfolio of his work, some of which was on his skin. He was offered a job but didn’t accept it for several months, “there was a lot of trepidation”.

Before blackwork had become established, Sparkes did Duncan X-style tattoos “slightly differently done”.

“I tried to do a Duncan/Hooper mix… I couldn’t go and get tattooed by Duncan and then show him tattoos that I was doing that were exactly like his… that would be just barefaced, shame faced.”

Sparkes’ work, he explains, was cut-down with lots of space around it, much like the minimalist line work tattoos now multiplying across social media as though a new trend: “That was what I was starting on and people were like, ‘that’s way too simple, that’s not even half finished… and there’s no colour in it’.”

Newly single, Sparkes’ partying found a “fifth gear” and he went “super hard” while hitting the road, often with Maxime Plescia-Buchi, whose geometric mastery has since seen him develop the tattooing Mecca that is Sang Bleu, and with other industry stalwarts, Guy Le Tattooer and Rafel Delalande.

He also began stints at East River Tattoo in New York where he has been a regular now for seven years.

“That escalated things a lot because people weren’t going to New York much as tattooers… people just weren’t travelling as much for tattooing in general, like majorly, like they are now. Chad Koeplinger was doing it a lot, he was my inspiration for travelling and also for tattooing.”

Sparkes, who by then had been fired from one band and quit another because “I was over it… I had been on the road touring, for like 10 years”, says he never saw tattooing as a “way to party” and to carry on the rock and roll lifestyle of his youth.

“Number one was always tattooing, just for tattooing. And it saved me in a lot of ways as well because I have those tendencies… so it just gave me the opportunity to grab life by the throat and do whatever I wanted.”

Sparkes continues: “One day I had the thought in my head, ‘what would I want to do if I could do anything I wanted, whenever I wanted’, and it would be to travel the world, you don’t worry about life, and go travelling, get fucked up, just do all the things I like to do. So I still respect tattooing for allowing me to do that. And that’s why I still have such a work ethic and common sense because otherwise you’d mash yourself up.”

Sparkes credits his appearance in Forever The New Tattoo as being an escalation point in his ascension: “It changed a lot of things and made us… it was kind of a compilation album with a lot of friends of mine. Every tattoo shop now has it. Things over-grounded after that. It was just an explosion of customers, I couldn’t not tattoo. It was a harvest. It was fucking insane. But at that time I was doing a lot of birds and flowers and things people kind of like.”

Sparkes’ style constantly evolves but the imagery has “always got worse”, he concedes. Super-minimalist pieces morphed into thicker-line engraving style tattoos before a “black-phase” – after meeting Guy and Raf – got out of hand, “I got really obsessed with blackening everything and that went over the top”. Now, Sparkes says his style is a “mix of all that – balance, contrast, obsessions”.

“You can’t do that stuff (brutal tattoos) without having a back-up, you know what I mean? I feel like I’ve come full circle. I’ve been able to do now what I wanted to do all along because I’ve done all that legwork, of just doing flowers and birds and what not. But I just don’t really believe in those tattoos anymore so I don’t want to do those things that I don’t believe in. Same with colour.”

Sparkes’ taste for the ugly comes down to a desire to make art that lasts and he credits Axl Rose as an early inspiration. The Guns N Roses singer’s tattoos were perfectly placed for maximum effect and like the crude works worn by criminals, “he just owned them… people need to own their tattoos”.

“It’s the same with the beautiful paintings and the beautiful tattoos. I appreciate them of course but you spend less of your time looking at them, I find. I’ve noticed, well, at least with me, I’ve found the amount of time I give a flawless tattoo, or a flawless painting with perfect brush strokes… it’s just false, it’s not the reality of things. Everything is imperfect. Life is imperfect.”

Tattooing, like everything in life, has been gentrified and debased but Sparkes has made peace with that rationalising it away as simply a consequence of there being “too many people in the world” – another of his obsessions: “I’m so upset. I think about it every day.”

When blackwork mainstreamed, however, Sparkes felt more personally violated:

“Tattooing for me was an obsession that became a need, rather than a want, and it was something very sacred for me, and at that time, when there was the explosion of all blackwork and stuff like that, for me, it felt like… I have no problem with it now… but at the time I felt like this path that I had found in this forest, this little pathway… and walking down its serene and it feels unexplored, you know, like when you’re a child finding this un-trodden path, and then suddenly people start walking on the path and littering everywhere and they make it look like shit. That’s how I used to feel. But now I don’t give a fuck. I used to have a big problem with that when a lot of copying began. But I have no authority over anyone because everyone is a copier. Now-a-days days there’s just a lot more people so there’s less chance of being original.”

Originality for Sparkes is what tattooing is about. It drives him and it pains him: “There’s some times, months to years, where I will be resting on my laurels. There has been over the past decade or whatever, times when I’ve just been coasting and I know it, or maybe I don’t. But you know everyone gets tired creatively.”

Life on the road was about pushing himself physically, and creatively – “it’s living, it’s really living” but Sparkes ultimately found it “lonely and soulless” which led to him opening Old Habits Tattoo in November 2015 (read about Sparkes’ decision to open the shop here).

“There’s the romanticism of it all and then there’s waking up in some shit bag room, whatever, in some other city, somewhere, looking yourself in the mirror… and you’ve just been up for days, or treating yourself like shit, and you just want to go home to your mum.”

Sparkes doesn’t “like mentioning on record” the depths to which his depravity has dived, but the delinquency is done simply for “fun” and the logic is as earnest as it is sound: “That’s all I’m trying to do. That’s the bottom line. I’m just laughing at life because it’s fucken brutal and absurd and I’m going to have some fun while I’m here. I like what they say in that book, ‘when you die, no one gives a fuck, so I’m going to have my fiestas when I am alive’. When it gets old and boring, I’ll stop.”